By Kathy Abascal

I often mention the Eclectic physicians in my articles because of their deep knowledge about medicinal plants. The Eclectics were licensed medical doctors who primarily used herbs and natural principles of healing to treat their patients. They were a strong force in American medicine from the 1830s to the early 1900s, but were driven out of medicine by the 1930s. Their views and practices differed greatly from the “regular” MDs who later formed the American Medical Association, and medicine as it is known today.

Consider this: On Friday, December 13, 1799, George Washington woke with a painful sore throat, labored breathing, and a fever. He had been soaked in a rainstorm the previous day. He called for a bleeder who took 12 or 14 ounces of blood from his arm. Washington felt worse the next day and called in his doctors. They prescribed two more bleedings, along with two doses of mercury and a cathartic enema. He grew worse. After some debate, his doctors decided to bleed Washington another 32 ounces, and gave him a much larger dose of mercury combined with a dose of antimony (another strong poison). Blisters were raised on his throat and the soles of his feet. On December 14, soon after awakening with a cold, George Washington was dead.

This “heroic medicine” was accepted medical treatment, and had been for centuries. King Louis XVI likely survived childhood only because his mother locked him away from the doctors who had bled and killed three other heirs to the throne. These practices continued in use for most of the 1800s. Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, taught medical school and advocated bloodletting for almost all conditions. He recommended drawing up to 140 ounces to cure pneumonia (the average adult has about 160 ounces of blood). He also taught that mercury was a “safe and nearly a universal medicine.”

In reaction to the “heroic” medical practices of “regular” MDs, a group of physicians created the Reform Medical Society of the United States and called themselves Eclectics from the Greek word meaning “select.” Their goal was to find the best remedy for each patient’s ailment by choosing carefully among available remedies, including those of the homeopathic MDs and Native Americans. Their primary medicines used were herbs. The Eclectics believed strongly in nourishing the patient rather than using bleeding, mercury, and antimony.

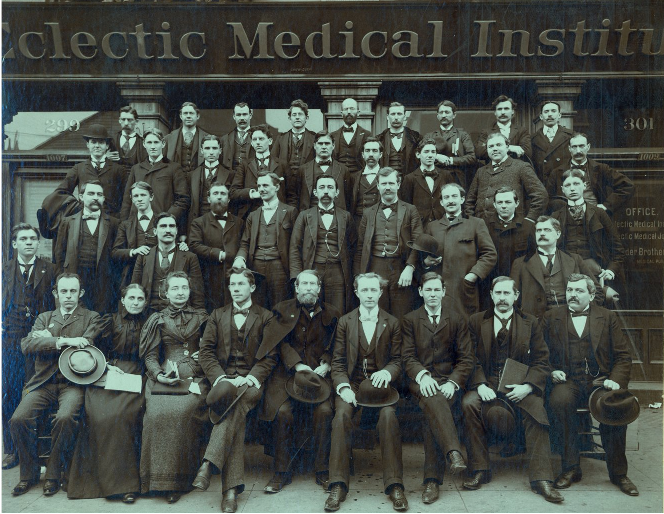

The Eclectics opened medical schools, and some of the first women and African American MDs were graduates of their schools. They published journals and gained the aid of John Uri Lloyd, a famous and very skilled pharmacist. Lloyd focused on how to make herbal extracts, working to create tinctures that retained the actions of the whole plant. Many tinctures sold today are still made according to his recommendations.

Eclectic books remain available, and detail how these physicians used plants in all aspects of medicine, from simple colds to serious heart ailments. The Eclectics sometimes struggled – as do modern herbalists – with the gentleness of their medicines compared to the strength of allopathic drugs. Thus, one Eclectic MD lamented: “Some people will take a few doses of medicine from an Eclectic, and if it does not cure at once, they think there is nothing in it. But they will take large doses of strong drugs week after week and though they do not improve they think it is all right because the medicine has a big bulk and a powerful taste. They think it is doing something. Well, so do we. It oftentimes gives the undertaker a job.”

So why have so few of us heard of the Eclectics? In large measure, that is due to a battle a man named Flexner waged against both Eclectic and the homeopathic MDs on behalf of the AMA. The public was left with the strong impression that plant medicines were both ineffective and dangerous, and that disease was never treated successfully before the advent of modern drugs.

And while some of our prescription drugs are truly wondrous, we have developed the habit of always looking for miracle drugs to fix any woes, big or small, rather than taking care of ourselves by learning when and how to use plants as food and medicine.