An Expert Interview About the Thunderbird Treatment Center

By Caitlin Rothermel

Dr Marli Parobek is a doctorally prepared nurse practitioner, board certified in family practice and psychiatry. Starting in 2018, she developed and managed a voluntary inpatient medical rehab/detox center (American Society of Addiction Medicine [ASAM] level 4.0 and 3.5) and an involuntary inpatient psychiatric unit at Astria Toppenish Hospital on the Yakama Indian Reservation. She also served for seven years as the sole prescriber for Yakama Nation Behavioral Health and completed an internship at Sundown M Ranch in Selah, WA (ASAM level 3.5).

Dr. Parobek has lived on Vashon for three years; she has a local private practice and also works with Vashon Youth and Family Services. Currently, Dr. Parobek is the only prescribing psychiatric professional on Vashon Island.

To prepare this article, I also talked with Neal Cotner, a licensed mental health consultant who currently works with the Fort Simcoe Job Corps Center and previously worked at the Astria Toppenish Hospital inpatient psychiatric unit.

Dr. Parobek and I discussed the medical needs of patients treated for addiction, the kinds of facilities that exist for treatment, and her concern that local residents and organizations have been denied meaningful discussion regarding the establishment of the Thunderbird Treatment Center on the Island.

What Patients Need

Dr. Parobek is concerned that the Thunderbird Center will find it impossible to maintain the staffing needed to run a site of this complexity, largely due to ongoing ferry difficulties and a lack of local housing. She is concerned that patients may not be adequately medically or mentally screened prior to being sent to Vashon for drug and alcohol rehabilitation.

“You absolutely need a psychiatrist to screen people when they come through. Unfortunately, 50% of people using a substance also have a mental health disorder … As people were discharged [from Astria Toppenish Hospital to the Sundown M Ranch], they remained oftentimes on Suboxone, benzodiazepines, or anti-psychotics.”

Mr. Cotner confirmed that substance abuse disorder combined with mental illness is a common patient profile, known as “co-ocurring disorders – two things at once.” Dr. Parobek further explained the process: “A psychiatric evaluation takes an hour. We have to be able to differentiate between schizophrenia and drug-induced psychosis, delusions, bipolar, bipolar with psychosis, depression, anxiety … [At Astria], I had patients who would bounce back all the time into the hospital [for mental health reasons], and that’s not going to be available on an isolated Island.”

The Thunderbird Center will also need a medical doctor and/or nurse practitioner, to manage daily care, in addition to nurses, case managers, therapists, social workers, and counselors.

Even at this post-detox point, substantial medical support is essential to patient safety. According to Mr. Cotner: “Virtually every person that comes through [treatment] is at fairly high risk of having some sort of medical compromise. If you’ve been drinking copious amounts of alcohol for long periods, there’s a good chance you’re going to have liver issues like fatty liver or cirrhosis. For patients who used methamphetamine, you’re always worried about cardiac concerns.”

Since Thunderbird proposes to house women with children, including pregnant women, a specialized obstetrician/gynecologist would also need to be on staff to help mother and infant through withdrawal; premature delivery would also be a risk for patients, and such situations would require immediate expert care.

Last, the site would need support staff, like janitors, cooks, and security guards.

Dr. Parobek asks us to consider whether the Vashon location was chosen out of considerations like medical practicality and the well-being of patients and their families, or for political reasons?

Because the Thunderbird Center can only be classified to operate as a low-intensity facility, Dr. Parobek also sees multiple potential points at which client health and safety could be compromised.

What Guidelines Exist?

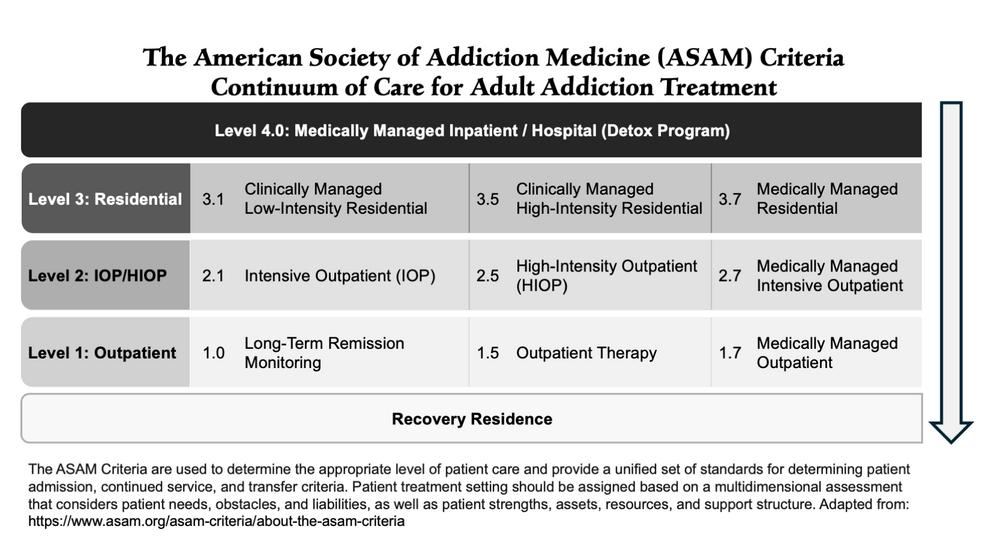

Dr. Parobek explained that many residential recovery services, including all such services in Washington state, operate on rules established by the ASAM, or American Society of Addiction Medicine. ASAM provides a structured “step-down” system of residential centers (see image), designed to provide patients with services that match the intensity of their needs.

For each residential center level, ASAM has requirements that include clinical, counseling, and security staffing. To retain licensing, residential sites must meet these criteria – not unlike how hospitals function.

ASAM residential sites are assigned numeric levels, starting at 4.0 – inpatient detox – this is the level of center that Dr. Parobek ran at Astria Toppenish. Patients typically receive initial care at level 4.0 facilities. These sites are often run out of a hospital; patients generally stay 3-7 days and have 24-7 access to emergency and other medical services.

Next down on the ASAM criteria are levels 3.7, 3.5, and 3.1. Sundown M Ranch is a level 3.5 facility, also known as “high-intensity” residential services. According to Dr. Parobek, “Sundown M has 24-7 therapists, security, nurses, nurse practitioners, and the physician. The reason the program is so successful is because it’s 30 minutes from a hospital.”

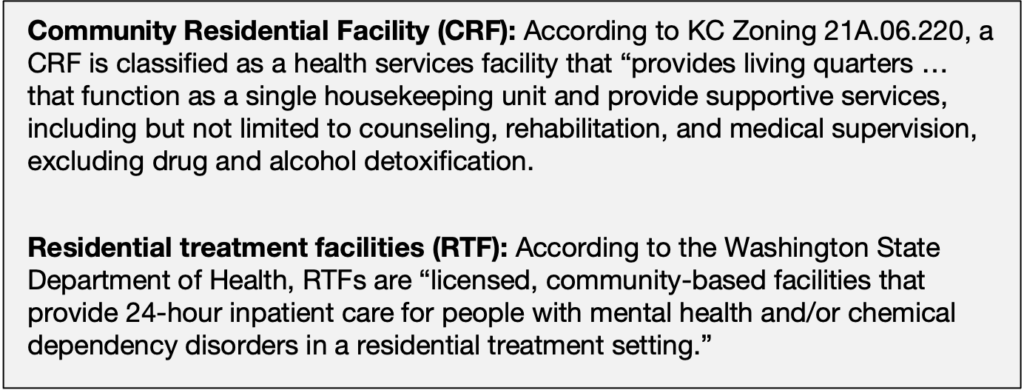

According to the SIHB website, the prior Thunderbird Center was also a level 3.5 facility. It’s worth noting that the requirements of a level 3.5 facility match well with the Washington state definition of a Residential Treatment Facility (RTF). An RTF is the facility type SIHB initially wished to apply as (see inset for definition).

The SIHB has announced that the proposed Vashon site will be ASAM levels 3.1 and 3.5, but according to Dr. Parobek, a residential center here would struggle to adequately meet ASAM 3.5-level care. She believes the SIHB is indicating they plan to operate the site at level 3.1, or as “low-intensity” residential services. ASAM level 3.1 somewhat matches the brief King County definition of a “Community Residential Facility” (CRF; see inset for definition), which SIHB is now applying as.

In a level 3.1 setting, patients are defined as being medically stable and receiving as-needed (as opposed to ongoing), medical care. A recent article in the Beachcomber also notes that, under CRF codes, the “Thunderbird Center will not be a ‘hospital’ … because it provides no diagnostic services.”

According to Dr. Parobek, “[With level 3.1], we look way down the [treatment] line, and that is like a counseling site. People are living there, eating there, sharing meals, going on walks.”

Dr. Parobek says there is a simple reason – patient safety – that no other Washington state drug and alcohol treatment centers in the upper 3 and 4 ASAM levels operate at this great of a distance from hospitals, clinics, urgent care, and emergency mental health services.

A Lack of Community Input

Many Vashon residents trying to understand this situation have found themselves confused and overwhelmed, and Dr. Parobek has input for them: “The reason there has been so much confusion is because there’s been absolutely no information, and that lies solely on King County and the Seattle Indian Health Board.”

What would be a more typical process used to introduce this type of treatment center into the community? Both Dr. Parobek and Mr. Cotner were part of the build-out of the Astria Toppenish program, and both recalled substantial, early community engagement that included multiple meetings, community forums, and meaningful needs assessments. Overall, a lot more genuine, good-faith interaction than Vashon has seen, even though we have requested it.

According to Dr. Parobek, the typical planning steps that occur are similar to when a large new business considers moving in. “It’s the same thing as if I came in and said, I want to take the old K2 factory and make it into an IKEA. Okay, what kind of impact will that have on the environment? What kind of jobs analysis do we need for an IKEA? Will the road be supported for the extra transportation?

“All of this would’ve been done, and there would’ve been several community meetings to let people know exactly what we were doing and why. It would be full disclosure: what it would look like, how much it would cost, where the money would come from, who would need to be employed, how much these people would be paid, what type of people would be brought in, and a risk assessment. What happens if this goes belly up, and now we have an empty building? What happens if you find out you don’t really need an IKEA?”

I asked Dr. Parobek – is it an objectively appropriate use of KC funds to open a drug treatment center on a relatively isolated, rural Island? She answered: “No. It would be more cost-effective to operate a drug rehab center in a location with affordable housing for staff, inexpensive and plentiful hotels for visiting family, 24-7 transportation by roads, and low-cost facility operating resources such as food, fuel and labor.”

A Pattern of Persistent Non-communication

Dr. Parobek shared with me that she and other Island groups and clinicians have reached out to SIHB – to ask questions and to offer to collaborate and share their experiences working on the Island.

“The SIHB has not involved any Vashon clinics to coordinate care, nor has SIHB or Teresa Mosqueda directly surveyed whether or not Islanders want or need this treatment center on Vashon.

“Like many Islanders, I attended meetings, optimistic that the SIHB had good intentions to be forthcoming with information and seek community input and involvement. However, when I emailed SIHB and offered to collaborate, I was dismissed and then finally ignored.

“After a disappointing email attempt to reach SIHB, I attended a Zoom Meeting with [KC Councilmember] Teresa Mosqueda on June 12th. Mainly, I reminded her that Vashon’s number one community health need is not drug rehab, but affordable housing, both long-term and emergency. Mosqueda was disinterested.”

Dr. Parobek’s repeated contacts with Mosqueda have left her frustrated with how little attention our local issues receive.

“I would encourage all Islanders to reject the ideology that we need to import KC politicians and special interest groups to improve our Island. We can make an impact by becoming involved with on-Island agencies that directly affect the health of Vashonites. These include DOVE, Vashon Youth and Family Services, Vashon Food Bank, Vashon Household, and the Interfaith Council to Prevent Homelessness.

“What do all of these agencies have in common? They serve people on island and were created organically by Vashonites.”