By Deborah Anderson

September 1969. I sat on the edge of my bed in my first year at Mills College for Women and said to myself, “It’s safe to be a woman here.” As with many of my epiphanies, I wasn’t sure how I knew that or why it was important, but it brought peace to my soul.

For the next four years, I lived passionately and eagerly in the intensity and excitement of ground zero for the Black, La Raza, and women’s movement/revolution. Professors who were changing the world and culture taught me critical thinking. This was it! Racism, sexism, and extraction capitalism were all coming to an end!

I got married the day before graduation, as one did in those days. Armed with a Theatre Performance degree and a California Nursery School Diploma (the equivalent of an Associate degree in Early Childhood Education), the world was filled with possibilities.

Children followed after a few years. I was answering a calling that started in Children’s Theatre and ended in the ministry. Busy, busy, busy.

While I was occupied, the women’s movement and racism seemed to go sideways. Both became monetized. Whether in sitcoms or movies or the music world, corporate leverage or sports, the moneymakers found they could make a buck by ostensibly presenting the marginalized as equals. Money was made, but the individuals headlining the shows or events rarely got an equal portion of the profits.

Sure, some men were in the woods beating their drums in circles to find themselves, and women were allowed to put on floppy bows and go to the office, but dominant colonial patriarchy didn’t change at its core, and women still made only cents on the dollars instead of actual dollars.

As a minister, I broke through the stained glass ceiling, but nobody sent the memo that this was a good thing, or prepared the previous generation for new leadership. So it was that a couple of 80 year-old men who did not like a woman telling them about God, and some women who had always stood by their men, ended the joyous party the rest of us were having.

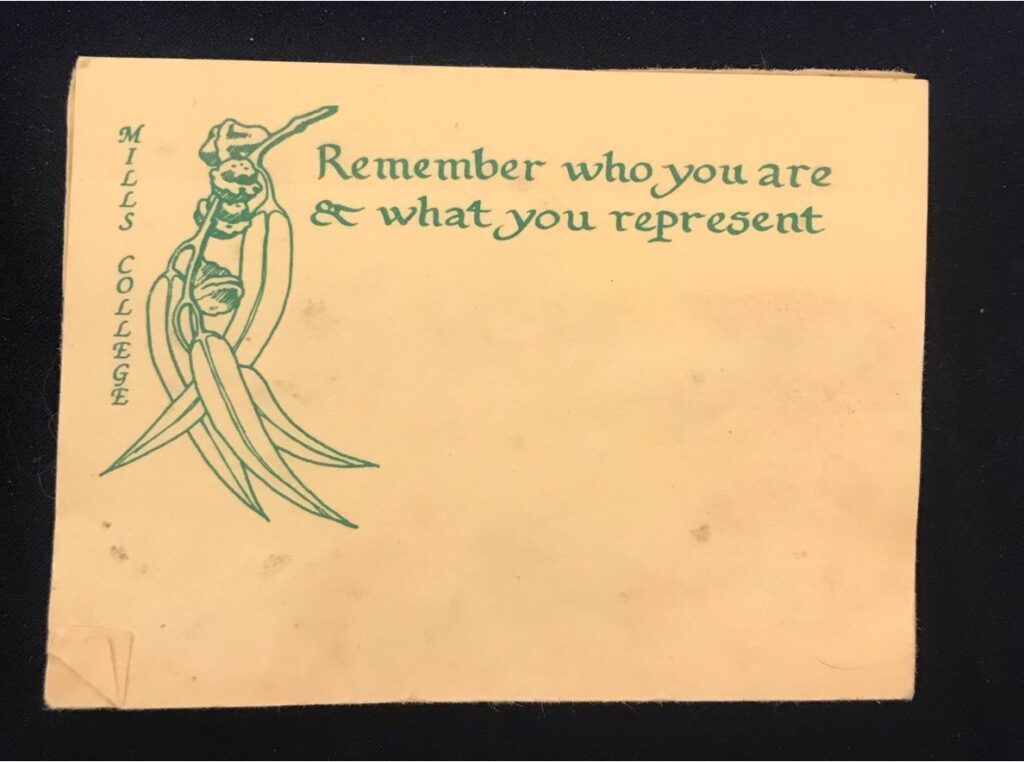

The first morning after I was ceremoniously dumped into homelessness with my two birth children in tow, I awoke at the home of a Mills alumnae sister who had taken us in. My eyes fell on a pad of Post-it notes the Palo Alto alumnus group had sold as a fundraiser. The curve of a branch of eucalyptus leaves with the words, “Remember who you are and what you represent.”

I took a deep breath. Find my core. Who am I? A woman who has been told and taught that I have the courage, critical thinking, and chutzpah to rise above and begin again. And what do I represent? The new possibilities of and for women.

The 80s and 90s were confusing. Women were at work, but still disproportionately carrying the burden of chores and childcare. The dot-com bust came just as conservative religion began to surge forward.

Meanwhile, Mills was struggling in baffling ways. In the 90s, it resisted the recommendation of the Board to go coed. Rumors of imminent financial ruin swirled. The Millenium brought a change of leadership at the top. As the first educational institution to accept trans students, the voices of opposition to the future began to be louder.

In 2021, the new President Beth Hillman announced a “merger” with Northeastern University, a Boston-based university now established as an educational franchise. With “campuses” that are really just a single, rented room in various cities – for example, the Seattle “campus” is a small room in a building on Terry Avenue that has a table, a dozen chairs, and a white board – Mill’s 127 acres of prime property in downtown Oakland, with all its assets, was like fresh meat to a shark in the water.

Yes, I did call Northeastern a shark, an economic shark, and after years of administrative mismanagement, Mills was bleeding green into the waters of higher education. In June 2022, Mills as we knew it was no longer.

Two mysteries remained. First, Mills was not actually in financial trouble. Its financial strength was hardier than 60% of colleges in the country at the time. The breadcrumbs tracing the path of people with fingers in a pot that was not theirs was more than visible. To further complicate the picture, 51% of Mills students were women of color.

The greater mystery was that women were the catalysts to this transaction. Women betraying other women pulsed like a neon sign in the old part of town. Class gifts given in support of the “merger.” The “Institute,” a leadership program for women of color that garnered the support of key alums, was actually some rooms in Mills Hall.

Where once women of color had 127 acres, accompanying assets, and brilliant professors to teach them in ways that would underscore and enhance their gifts and talents, now they were given seed money to form their own program. Money that, like the name Mills itself, was scheduled to run out in two or three years.

Right now, women are divided in strong and unhelpful ways in the country, the state, this Island. Women who want equal access and freedom to everything men have, and women who want very little but for the price of groceries to come down. Newly labelled Trad wives, and single women with a strong desire to avoid children at all costs. Hybrid women who want a little of everything, and single moms just trying to keep the boat afloat and moving forward.

We need to join forces and find a way to talk together. I have some ideas about where we could rewind and revisit for a do-over, but mostly I think we have stuck with our own kind and not conversed across differences in respectful ways. Never has the imperative been stronger for women to unite. Everything is at stake. Turn to your neighbor and say, “Let’s talk.” Please.

For generations to come, we need to start dissembling the fences over which we have sometimes passed pleasantries and begin real discussions, complicated conversations. I truly believe, as women, we can learn to do that. Let us begin.