By Caitlin Rothermel

You are probably outsourcing too many of your health care decisions, and your health plan is one of the biggest drivers of both the costs and choices you are and are not allowed to make.

It’s no secret that the price of Affordable Care Act (ACA) health plans is increasingly untenable. It’s been rough going for employers purchasing group health plans and for people purchasing plans on the individual marketplace. In Washington State, individual ACA plan premiums have increased by 8% per year over the last two years

Open enrollment is approaching again, and things are going to become more intense. In 2025-2026, small business plan premiums will increase by 6-16%, and individual plans by an average of 21%. Why? Partly, it’s due to very large and apparently unanticipated increases in medical care costs for ACA customers.

Exemplifying this, in July 2025, one major U.S. insurer (Centene) posted losses so high ($1.8 billion) it drove down the stock value of the entire sector. Centene has since announced that it is “in the process of requesting premium increases for Obamacare plans for 2026 to reflect a higher proportion of sicker patients who need more medical care than it previously expected.”

But increased spending by insurers is only part of the story. In addition to the original subsidies provided to lower-income individuals when the ACA was passed, additional tax credits, designed to be temporary, were put in place during COVID time. These subsidies adjusted premium costs based on monthly income, and benefited 81% of individual Washington state purchasers. But these subsidies expire this year, and it’s not clear at all whether they will be renewed.

If the subsidies are not renewed, the Kaiser Family Foundation has modeled the combined impact of this loss alongside premium inflation, and estimates an average 75% increase in premium costs in the individual U.S. market. Based on this, it’s expected that 80,000 Washington state residents – primarily healthier people with moderate incomes – will drop their health insurance this year.

The rising cost of health coverage is disturbing. Equally disturbing is how little you get for it. Hard-working families are being asked to pay premiums that rival their housing costs, yet each year they receive less coverage and shoulder more out-of-pocket costs. High deductibles mean that even routine medical visits require careful planning and budgeting, with the upshot being that many now hesitate to access basic care.

This leaves many in the position of paying hefty monthly bills primarily as protection against a potential catastrophic event. At the same time, more and more physicians are – for valid reasons – refusing to work directly with health plans because reimbursement is both low and unpredictable. Plus, if you prefer to rely on alternative health care options, those are likely to not be covered at all.

This is no way to live, but what choice do you have, especially if you have a family? One option more people are turning to is health care cost-sharing. These are systems in which participants collectively share medical expenses instead of paying traditional insurance premiums.

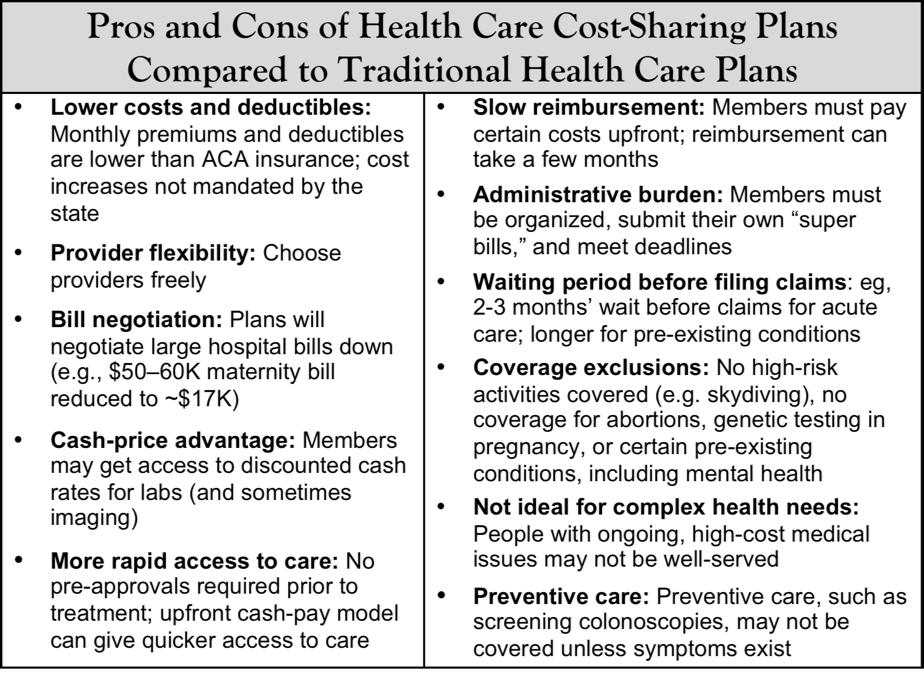

I spoke with two Vashon families who have relied on such plans for several years. I wanted to understand why they made the switch, how the model works for them, and the advantages and drawbacks they’ve observed with this approach compared to traditional insurance (see the table accompanying this article for a succinct list of the pros and cons).

Dr. Leigh Siergiewicz, a naturopathic doctor, and her family have used Liberty HealthShare for about seven years. Leigh has strong feelings about traditional insurance, “We do not like to participate in organized crime. If insurance CEOs are making $60 million a year and then don’t want to pay for anything for their customers, I don’t want to be part of that.” Practically speaking, Leigh and her husband reached a decision point when “the cost of the marketplace premiums and deductibles became about 30% of our income total before anything was even covered.”

They chose Liberty because it was one of the older, more established health-sharing programs. Currently, they pay premiums about $700 per month for a family of four, with a deductible of $2,500-$3,500. Each month, their payment goes directly to Liberty, and the organization uses those funds to cover medical expenses across its membership pool.

When it comes time to submit a claim, Leigh either pays out-of-pocket and sends Liberty a “super bill” for reimbursement, or – if the bill is large, like a hospital stay – Liberty handles negotiations and payment directly with the provider. In practice, this means Leigh often receives lower, cash-payer rates for services such as lab work, and in more complex situations, Liberty’s negotiators work to reduce charges before bills are paid. In Leigh’s case, this included negotiating a hospital bill of roughly $50,000 at the time of her child’s birth down to about $17,000.

Established in 1995, Liberty is run by the Mennonite church, but members are not required to be religious, although they must agree to a statement related to maintaining a healthy lifestyle, personal rights and liberties, and the obligation to assist others in need. When Leigh was doing her original research, she looked at some non-religious programs, but many of these were brand new. This is an important consideration, as Leigh has seen some of the plans she originally reviewed subsequently fail.

Another plan Vashon residents are using is Samaritan HealthShare, a Christian ministry established in 1994 where members support one another’s medical expenses. Each month, instead of sending money to a central office, members are assigned another household and mail their “share” directly, often with a personal note or prayer attached. Membership in Samaritan requires signing a statement of faith, having a pastor or priest sign an annual confirmation letter, and agreeing to certain lifestyle standards.

Jonathan (not his real name) and his wife chose Samaritan about five years ago after years of watching their individual insurance premiums climb steeply under the ACA, even as coverage eroded. As self-employed small business owners, they faced marketplace policies costing nearly $20,000 annually with high deductibles.

Although the ACA restricts enrollment to set periods, Jonathan argues that its guarantee of coverage regardless of health status eroded the traditional risk-sharing model and undercut the very principle of insurance. “When you buy homeowner’s or auto insurance, you have to buy it before the accident or the fire. With the ACA it became, oh, I was just diagnosed with cancer, I can go get insurance now.”

This shift transformed insurance into a “discount program,” and accelerated a cycle in which sicker individuals stay in the pool while healthier ones opt out, driving costs ever higher. This dynamic undermines insurers’ ability to balance premiums across a broad base of healthy enrollees, and fuels a cycle of “adverse selection” we are now seeing play out – higher costs lead to higher premiums, driving more healthy people out of the market, further weakening the pool, in an ongoing loop.

With Samaritan, preexisting conditions are excluded at entry, and certain situations (e.g., injuries related to alcohol) are not covered. Jonathan’s family has filed successful claims, including a breast lump workup and knee surgery. While upfront cash payment is required, reimbursement from members generally follows within a few months. For Jonathan, the tradeoff feels worthwhile – he avoids the “insanity” of rising ACA premiums and instead participates in a system he views as more transparent and community-driven.

For older individuals, turning 65 doesn’t necessarily mean leaving a health share program. Many plans now offer options that work alongside Medicare, helping to cover out-of-pocket costs rather than replacing government coverage entirely. Certain employers can also take advantage of this model: small businesses with ≤50 employees are not required under the ACA to provide health insurance, which means they can legally offer stipends or self-funded allowances to help workers with medical expenses. Employees may then use those funds to join health care sharing plans. The caveat is that these plans are not legally considered insurance, so the contributions don’t carry the same tax advantages as ACA-compliant coverage.

Leigh and Jonathan’s experiences with health care cost sharing plans underscore a broader trend. Had the ACA never passed, grassroots alternative approaches would almost certainly have emerged to address the crisis of affordability – and in many ways, that’s what is happening now. Healthier individuals are peeling off, while those with chronic conditions remain in ACA plans because they need guaranteed coverage.

Critics may argue this creates an unfair, two-tier system, with the sick “trapped” in an ever-shrinking and more expensive pool as the healthy “jump ship.” Yet, the ACA itself set these incentives in motion by eliminating preexisting condition exclusions without building a sustainable way to balance the risk pool. The result is a system inevitably designed to strain under its own weight – those who most need healthcare are left with increasingly costly plans, while others seek relief and alternative options.

In the end, this division is not just a problem for one side or the other – it is a structural flaw that threatens the stability of healthcare financing for everyone.