By Caitlin Rothermel

Last month’s article looked at the increase in myocarditis in the United States since the COVID-19 pandemic. Among young men in particular, vaccine-induced myocarditis seems to have at least doubled. This month, I looked at some new research that used national vaccine databases to study patients who developed myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination.

A study published in January 2024 used a “big picture” historical perspective to understand vaccine-associated myocarditis. Researchers looked at all myocarditis events reported to the U.S. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) from 1990, when the database was started, to August 2023.

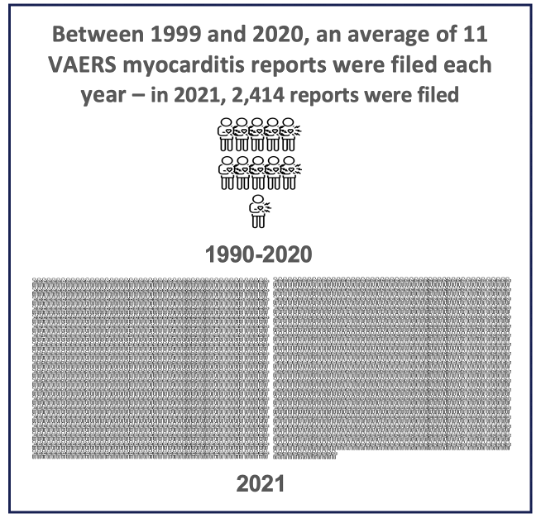

Of the millions of events reported through 2023, only a small percentage were for myocarditis – 3,078, or 0.3%. But nearly all of these myocarditis reports were filed in 2021 – 2,414, or 78%. Put another way, between 1990 and 2020, an average of 11 myocarditis reports were filed each year, but in 2021, this rose to 2,414 (and continued at high rates in 2022 and 2023).

VAERS reports are designed to tell a “medical story” of what happens after vaccination – when the problem started, what went wrong, and how it resolved. Looking at these VAERS myocarditis patients, one-half were children and adults younger than 30, and 69% were men. Three-quarters (76%) of patients needed emergency care and/or hospitalization, and 3% were deaths. There was greater risk after the second dose, something that’s been shown in previous research.

In another story, last month in social media, we learned that the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention responded to a Freedom of Information Act request with a fully redacted (ie, purposefully blank) 148-page document. The FOIA had requested long-term data from the “MOVING” study. (MOVING is meant to be an acronym for “Myocarditis Outcomes After mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination Investigators and the CDC COVID-19 Response Team.”)

Sponsored by the CDC, MOVING looked at young people (aged 12 to 29) diagnosed with myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination. Patients were found by searching VAERS myocarditis reports. The researchers used CDC criteria to confirm the myocarditis diagnosis, and directly contacted patients and their doctors to ask if they would take part in a survey interview process that covered patients’ symptoms, quality of life, and medical records, as well as how well patients’ doctors thought their recovery was going.

Noteworthy to me was that the CDC felt comfortable using VAERS for this research. Despite being a federal database that clinicians and patients are encouraged to use to report vaccine-related adverse events, VAERS has been labeled “unreliable” and “unverified.” As recently as February this year, a CDC representative was quoted as saying, “VAERS is … not the dataset we use to determine causality or the impact of the vaccine.”

In actuality, even though VAERS doesn’t include information for all patients – a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report found that VAERS contained “fewer than 1% of vaccine adverse events” – VAERS data can be predictably used to estimate serious adverse events.

Back to the MOVING study: Of the 836 patients found eligible through VAERS, two-thirds responded to the invitation; the others could not be reached or didn’t want to participate. The studies’ initial published resultswere optimistic – of the 393 patients whose doctors responded, 81% were considered “fully” or “probably” recovered at about 90 days. At that time, 68% of patients were cleared to engage in all physical activities, and 26% were still taking medication to manage their myocarditis.

That was part one of MOVING. It ended in January 2022, with results published 10 months later. The last sentence of the published manuscript introduces MOVING part two: “The CDC is conducting additional follow-up on patients who were not considered recovered at least 12 months since symptom onset, to better understand their longer-term outcomes.” This one-year MOVING data is what was requested from the CDC by FOIA, and we apparently are not allowed to see it?

The CDC may have planned to publish these MOVING results and not wanted them seen until finalized. In fact, the FOIA exemption code used suggested just this. But MOVING part two would have ended in January 2023. For how long should the public be expected to wait? Also, searching online, I couldn’t find any recent updates about MOVING. Quite the opposite: a September 2023 CDC summary only mentions the existence of MOVING part one.

A study from Australia gives some insight into what we don’t know about how these patients are doing – longer term. Conducted using the national Surveillance of Adverse Events Following Vaccination in the Community (SAFEVIC) database, this research looked at 67 teenagers and adults with post-COVD vaccination myocarditis, all treated at the same hospital. At about a year to a year-and-a-half after their diagnosis, on medical imaging, 30% had signs of heart scarring and ongoing disease.

There is one more important myocarditis story to tell – do the benefits of the injection outweigh the risks, at least in terms of myocarditis? Next month, I will return to this.