By Daniel Hooker

We in society have been molded and shaped into a form by words on paper, visual art, and music that resonates in our souls.

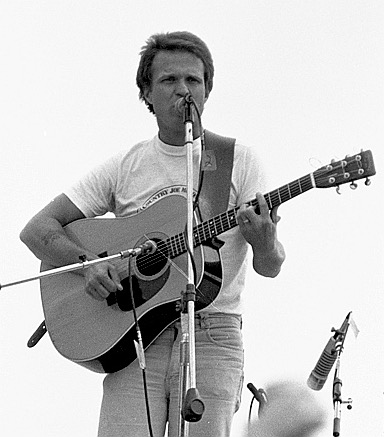

When I was a young man, I returned from Europe, with my mind, body and soul changed by all that I had experienced. I came home to a little coastal community called Bolinas in California, a town that saved itself through art and music. It was place where I would meet a musical influencer of the sixties and seventies, Country Joe McDonald, one of the musicians who graced the stage of Woodstock with his iconic song, “I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” that satirizes the horrible war in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Joe McDonald would stop and chat with me in the streets of Bolinas for 15-30 minutes, unhampered by time, always being present and in the moment. Seven years would pass until we met again, not by chance, but by the grace and forethought of my German wife, Uta, who knew I knew him from Bolinas.

I had seen a poster in the town square of Erlangen, Germany, and pointed it out to her (this was in July, and the concert was in December). By the time I had returned to Germany from California, my life had changed from being an able-bodied man to one who had undergone knee surgery and had become a father-to-be.

One evening, Uta announced to me, “Get dressed up. We are going out!”

Our unscheduled night outing had me nervous, as it involved a drive in the snow to the outskirts of Nuremberg. As the miles went by, finally, we arrived at our destination, a beer hall with a billboard declaring that Country Joe McDonald was playing tonight. My eyes got wide, my heart beat with anticipation of hearing a friend (acquaintance) from sleepy Bolinas, California. Except for the concert video of Woodstock, I had never heard Country Joe perform, and this night was a new experience that would forever change my view of music.

The first set was slow, with the hall partially packed with 80-100 people (with the capacity for 300-400). The crowd was less than enthused, only knowing a legend from the Woodstock film.

During the break, I walked up to Joe, and tapped him on the shoulder, saying, “How’s it goin’, Joe?”

Joe spun around, recognizing my voice, his eyes and face beaming with delight, questioning the reality of a face so out of place, from a town thousands of miles away.

Joe said, “What the hell are you doing here!”

I explained that I had just gotten married, that my wife and I were expecting a child, and she had bought tickets to his show. Joe and I caught up. Leaving me, he walked up on the stage, instructed that the spotlights be directed towards my wife and I, then he introduced us. “I would like to give a shout out to my friend, Daniel Hooker and his wife, Uta, from Bolinas, California, who are expecting their first child!”

With this introduction the small crowd erupted in cheers and applause, changing the dynamic and the connection to the artist featured there that night. Joe announced, “The next five songs are dedicated to my friends, Daniel and Uta.”

After this intro, the spirit of the concert changed, and instead of 100 people listening to bygone music, the energy shifted to a feeling of a sold out concert, where everyone knew the words of each song being played.

Music and art moves us, connects us, as a human race, through spirit, through its beating heart. The power of art and music

Recently, I interviewed musician Colin Andrews and Island musician Gregg Curry. They passionately spoke about the role of music in influencing the mood of films we have enjoyed throughout life, the nuances of each scene being brought closer to our emotional mood by the music, while anchoring our hearts in the moment. Collin spoke about how a movie with the proper orchestration delivers the passion of each scene, moving us into an alternate universe, experienced through emotions and celluloid.

Gregg Curry’s interpretation of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” spoke of Jack Nicholson’s portrait of a man changing the perception of the patients in an unkind institution, with strict rules and severe punishments that divided humans from humanity. Curry talks about the pivotal moment where Jack’s character points out that, if he can manage to lift and disconnect a utility sink from the institution’s floor, they, as a collective, might toss it through a window, creating a means to escape the institution.

None of the patients come to help. Jack’s disobedience is met by the inevitable. He is silenced with a lobotomy, and seeing this, Chief, the Indian character in the film, tears the sink up from the floor, and, tossing it through the caged window, breaks free of his institutional life. Claiming his freedom, he runs into the forest alone.

Gregg said, “For an artist to impact the world, they must first transform themselves – make the world you want be true in you. Then live that world and express that world in the wider world. The life you live is the art you create and the world you make.”

Gregg’s point is that one man can have a vision to change something but until we as a collective society make the actual movement of changing our circumstances, we are nothing but – and these are my words – “a pond of stagnant water.”

Through the experience of the film, empathy is transferred into our hearts.

How does the influence of art and music, move us into adjacent realms of reality? This is what I want to explore with my readers, my community of artists and musicians.

From spiritual beliefs, meditation practice, and purpose, how are our vibrational hearts moved? How do we as humanity evolve and resonate as glasses of water, filled up and played as if by a fingerprint lightly circling our glass of life?